Foreword: This script was written in the late summer of 2022. I was going to make it into a video, but given the direction I wanted to take my channel at that point, I didn’t feel it was appropriate. I still love this film, though.

KEATING

Gentlemen, open your text to page

twenty-one of the introduction.

Mr. Perry, will you read the opening

paragraph of the preface, entitled

“Understanding Poetry”?

NEIL

Understanding Poetry, by Dr. J. Evans

Pritchard, Ph.D. ‘To fully understand

poetry, we must first be fluent with

its meter, rhyme, and figures of speech.

Then ask two questions: One, how artfully

has the objective of the poem been

rendered, and two, how important is that

objective. Question one rates the poem’s

perfection, question two rates its

importance. And once these questions have

been answered, determining a poem’s greatness

becomes a relatively simple matter.’

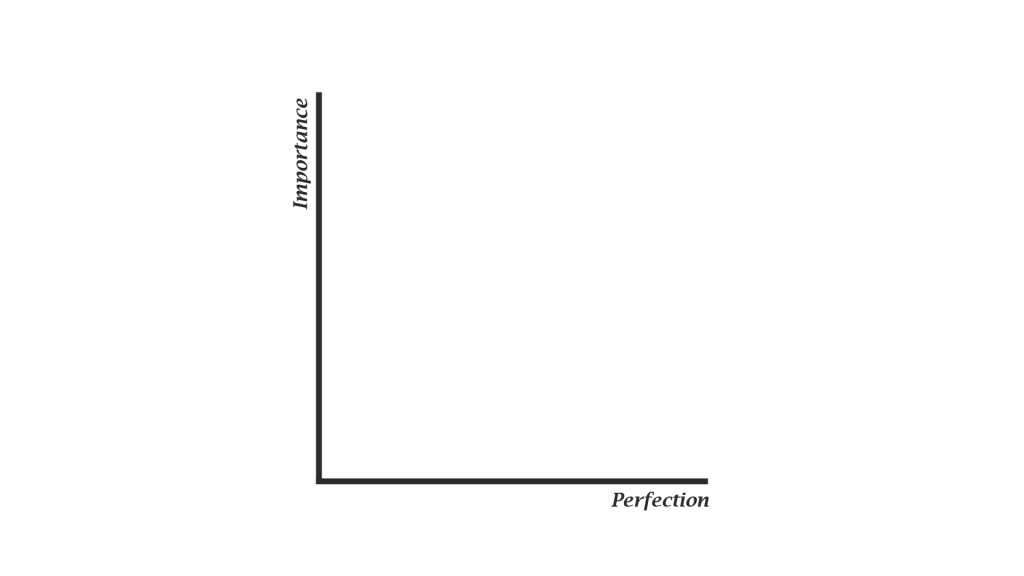

‘If the poem’s score for perfection is

plotted along the horizontal of a graph,

and its importance is plotted on the

vertical, then calculating the total

area of the poem yields the measure of its greatness.’

‘A sonnet by Byron may score high on the

vertical, but only average on the

horizontal. A Shakespearean sonnet, on

the other hand, would score high both

horizontally and vertically, yielding a

massive total area, thereby revealing the

poem to be truly great. As you proceed

through the poetry in this book, practice

this rating method. As your ability to

evaluate poems in this matter grows, so

will – so will your enjoyment and

understanding of poetry.’

KEATING

Excrement. That’s what I think of Mr. J. Evans Pritchard.

Nobody who has watched the Dead Poets Society could ever forget the iconic lesson Keating gives where all the boys rip out the pages of their English textbooks together. Some are all too happy to oblige, others worry about expulsion. All the while their teacher incites romantic verse which depicts literature as a war through which the raw reflection of the self is truly realised.

The writer which Keating so vehemently disagrees with is called “Dr. J. Evans-Pritchard”, and he writes in a way that feels sterile but otherwise academically rigourous, juxtaposed harshly against the language preferred by Keating. It’s an iconic scene, and sets the tone for the rest of Keating’s teachings.

When watching the film, I thought that such an approach was quite a strange way to evaluate poetry, and thought that surely it had to be made up. I looked him up, and it turns out that Dr. J. Evans-Pritchard is, unsurprisingly, a fictional author.

However, Professor Laurence Perrine, the author of “Sound and Sense: An Introduction to Poetry”, wrote a remarkably similar passage in 1956:

“In judging a poem, as in judging any work of art, we need to ask three basic questions:

(1) What is its central purpose?

(2) How fully has this purpose been accomplished?

(3) How important is this purpose?”

“The first question we need to answer in order to understand the poem. The last two questions are those by which we evaluate it. The first of these measures the poem on a scale of perfection. The second measures it on a scale of significance.”

“And, just as the area of a rectangle is determined by multiplying its measurements on two scales, breadth and height, so the greatness of a poem is determined by multiplying its measurements on two scales, perfection and significance. If the poem measures well on the first of these scales, we call it a good poem, at least of its kind. If it measures well on both scales, we call it a great poem.”

The Pritchard scale – or, in this case, the Perrine scale – is based on a real academic tradition. It is ardently defended online; ironically, this teacher sees value in it, while others have since found new uses for the scale. While it may have some niche potential here and there, it seemed (at least to me) like a pretty reductive way to engage with content of any kind.

Admittedly taking Perrine somewhat out of context (who himself claimed such measurements only provide value for newcomers to poetry), I decided to test the scale myself. I scored three poets on the Pritchard scale to try and better understand it’s purpose and potential merit.

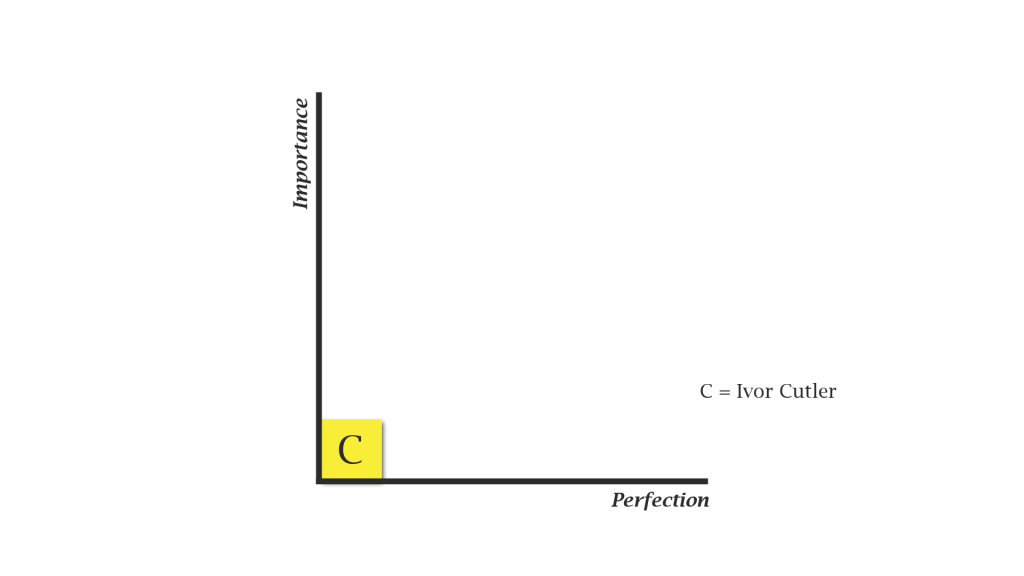

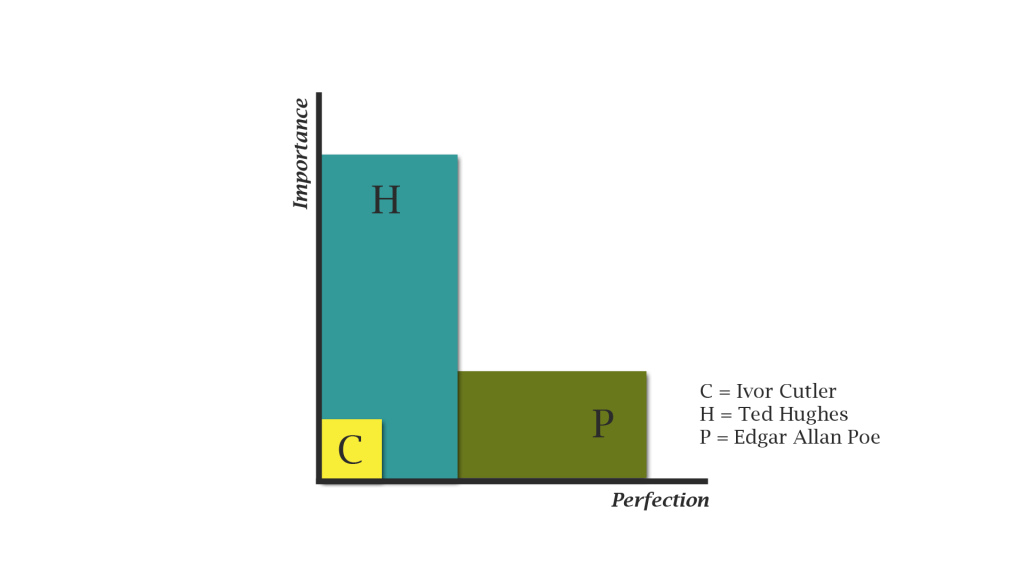

The poets I chose were:

- Ivor Cutler, a Scottish writer who mostly writes humourous nonsense poems

- Ted Hughes, a prolific British writer, famous for his war poetry and his nature poems

- and Edgar Allan Poe, a poet well and truly embedded in the canon of American literature.

I encourage you to follow along with authors you’ve read and see what it’s like to rate poems (or any literature, really) in this manner.

The works of Ivor Cutler scored low on both axes, which should be of no surprise to anyone familiar with his work, and would indeed be far from a surprise for Cutler himself. He loved to write about the little things and the silly things, and he does so in a way which encapsulates their otherwise overlooked yet compelling qualities.

His musings over the duller side of nature present an undeniably simple yet novel way of looking at life, bringing new insights to aspects of the world which would otherwise be quite mundane. Most of his poetry is just bizarre, really, but even then, it reflects a genuine appreciation for some of the most basic things we might otherwise ignore in our day to day.

However, as seen on the Pritchard scale, for anything to be rendered “truly great”, it cannot engage with the trivial – even if the insights we might have to offer on the trivial can bring us a refreshed perspective on life as a whole.

Speaking of a refreshed perspective – standing on desks, and the like – in some weird ways, Cutler has certain parallels to Keating. They both had their time teaching in the humanities and encouraged students in their creative pursuits. Ivor was intensely opposed to corporeal punishment and rejected conformity in much the same way Keating did. It comes as no surprise, then, that the Pritchard scale doesn’t get along with Cutler all too well.

The works of Ted Hughes get on with the Pritchard scale a little better, generally scoring well on the importance axis. Hughes is a renowned war poet, known for works such as “Bayonet Charge” and “The Casualty“. He also wrote extensively about the natural world and expressed sympathies towards various environmental concerns, particularly in poems like “Pike“.

However, the way in which he wrote was far from traditional. As an English student at Cambridge, Hughes had trouble adapting and appreciating the literary traditions of old, finding them stifling and confusing. Only by staying true to his own style did he write great poetry – or rather, did he write any poetry at all.

Again, however, the Pritchard scale discourages this kind of approach: sentences broken across stanzas, condense free verse, written in a way that is very personal but still offers great insights into a broad range of salient topics.

Crow is perhaps the best example of Hughes’ unique style, taking on an incredibly unorthodox perspective – and a voice that would prove to be divisive among critics – which allowed him to challenge and unify different narratives concerning religion and mythology. His reluctance to indulge in the usual rules of poetry and his willingness to experiment when crafting a unique message ends up hindering his potential for achieving greatness on the Pritchard scale.

The poetry of Edgar Allan Poe also gets on slightly better with the Pritchard scale, scoring highly on perfection but somewhat low on importance. Poe’s poetry is delightfully captivating – but unlike Hughes, who was especially concerned with constructing effective societal allegories in his poetry to prove a point, Poe was ready to write poems about almost anything.

While much of his work raised questions about big themes – particularly death and it’s relationship with life (or if we are even truly alive at all) – a notable portion of his poems make no effort to cover anything grand. His Enigma poems, published 15 years apart, make for an obvious example, and are fun to investigate.

Dream-Land is a personal favourite; one can physically feel the footsteps as the depicted traveler wanders through life. Poe wrote many poems for others in his life, written for and dedicated to them personally. But despite this, Pritchard would only be willing to call them “good poems, at least of their kind”.

Despite this, Poe situated himself as one of the leading Gothic writers of the era. His literary influence spanned across many American genres, propelling science fiction and kick-starting the tradition of the American short story.

Rather than trying to craft a grand narrative about how the world looked and how we ought to perceive it, he spent time working on new, growing (and, at the time, risky) genres. But as a result, the importance of his ‘purpose’ as understood by Pritchard is certainly contestable – and as such, his style of work is also somewhat discouraged by the scale.

So far, I had learned that the Pritchard scale punished a lot of the poetry I felt a connection to. I felt that it had forced my conception of art into one that concerns what is grand, rather than what we might value on a personal level. After evaluating all of this, I decided to add one more poet to the scale, to investigate and understand what a poem that was “truly great” by this standard might look like.

I thought the works of Wilfred Owen would be a good choice – important poems written at the height of wartime, highlighting devastation on the front lines, written in a conventional and clear, rhythmic style. Owen would easily score highly on both axes of importance and perfection, getting on with the Pritchard scale especially well.

But ultimately, the Pritchard scale still does not help us understand why the works of Owen are “truly great”. For us to understand that, we have to understand the author. The greatness of his poetry arose from his own experiences – he felt an obligation to share what he had seen in the trenches, to immortalize the horrific conditions he met with.

Owen encapsulated the tragedy in the best way he personally could: in literary form. He adopted certain themes and techniques not because they were ‘good’, but because he felt they were well placed to emulate the harsh reality of war. It is his rough experience and his brutal honesty which we value in his poetry.

When ranking all of these authors, I constantly found myself thinking about what other people think – or at least, what other people ought to think – about poetry. Rarely was I concerned about how good I personally felt the poems were, or how important they were to me, let alone how the poets themselves were actually connected to the poems they created.

Instead, I looked to the claims of literary critics to evaluate their alleged perfection, and turned to largely arbitrary rankings of importance based on the scope of the themes said poets usually covered. I’m still really not sure I came to the ‘correct’ answer on these scales, and I’m certain that some will leap to attack my decisions here – but they didn’t even feel like my own decisions to begin with.

It felt odd to essentially ignore my own opinion. In most cases, all the Pritchard scale managed to do was help me find ways to ignore the insights a poem might otherwise offer me. And in the single case that it was truly reflective of an authors ‘greatness’, it was still quite clear that the author had no intention to craft a poem through the approach that Pritchard had set out.

Going back to the film: what does this reveal when we’re watching Keating’s class? On the surface, this scene in the Dead Poets Society showcases Keating’s disdain for academic conformity and shows off his unorthodox approach. But after a further reading into the Pritchard scale, we see how this scene also highlights the importance of individuality, and why we should be wary of all those who try to beat that individuality out of us.

The Pritchard scale encourages us to ignore the unique message of the writer and has us constantly concerned with the broader canon of poetic literature. More than anything, it discourages us from making a personal connection to the poetry which we read. To some extent, it stops us from thinking freely about what we consume.

As Keating says, it’s not so much about what kind of verse you can write to impress others, but it’s about why you, personally, want to write in the first place. He wants us to speak from the heart, from our own experiences.

He asks us, “what will your verse be?”