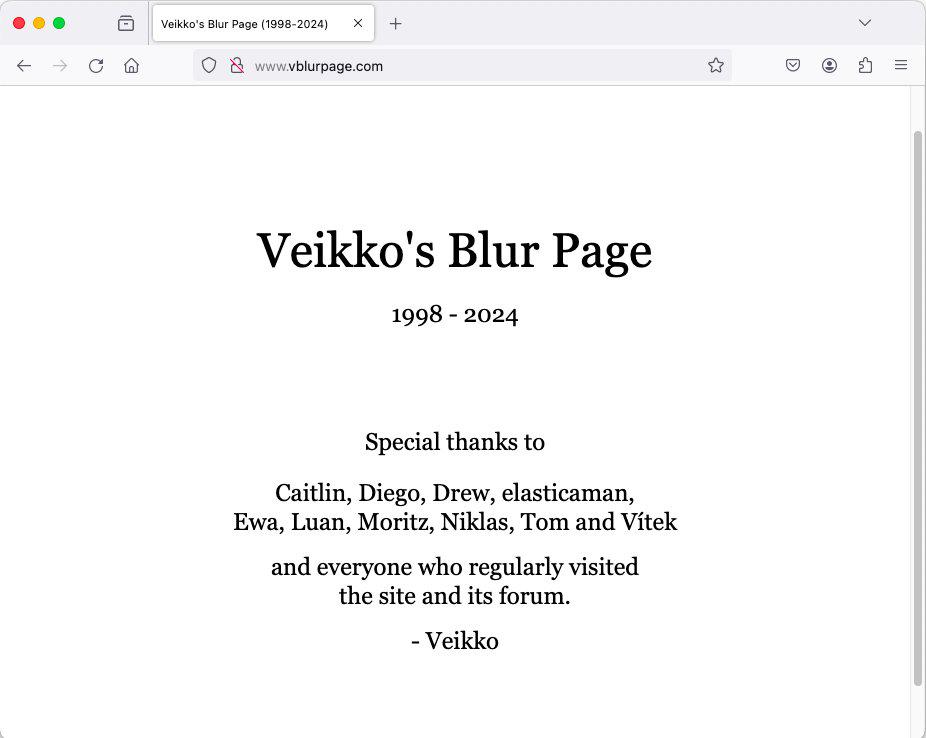

For the Blur community, today marks a sad but inevitable event: the closure of Veikko’s Blur Page (www.vblurpage.com). Having run for an impressive 26 years, Veikko’s page is a historic one. It was one of the first fan pages of its kind, near-religiously updated by a group of dedicated volunteers constantly providing up to date, accurate info about the band and its members. Its loss is a great shame – and is perhaps indicative of a wider problem when it comes to the future of hosting wiki-style pages.

The closure of Veikko’s page was originally announced in August 2023, however this somehow went unnoticed on my end. I first discovered the site when I became a Blur fan in my mid-teens (sometime around 2018, I think) and found it both incredibly useful and very interesting. I was running a modest fan page of my own on Twitter at the time (which can still be found: @oocblur) and consulted the site on many occasions for potential material and general info about the band.

I wouldn’t call myself the biggest fan of Veikko’s page, nor am I hugely affected by this news; I was never active on the forums and I don’t really run that fanpage anymore. It holds a special place for me though, since I co-opted the owner’s Finnish name for my own internet handle, combining it with an embarrassing moniker I had been lugging around for years before then (“munchmario” or “munchm”, a terrible name…). That new alias was ‘meikkon’, and it’s stuck ever since.

This post isn’t about me getting all sentimental for a site I forgot to visit. The closure of Veikko’s Blur Page is shrouded in mystery and nobody is fully sure (aside from Veikko himself, presumably) as to why the site was forced to close. The only reason given by Veikko is a vague allusion to copyright issues, but apparently not from takedowns issued by the band themselves (or their management).

You may notice that I’m linking a Reddit re-post here. I’d rather not do that, but the Wayback Machine doesn’t have this discussion screencapped. A lot of the forum has been lost now that Veikko’s page has gone down, including Veikko’s own profile. This makes it much harder for a latecomer like myself to understand exactly what happened here. But that’s not my main concern today.

I’m worried because Veikko’s Blur Page (or VBP, as we might abbreviate it) was huge, yet at the drop of an unknown takedown request, was forced to shut its doors to the public. I’m not kidding when I say VBP was the best Blur resource out there. I’ll let the archived about page speak for itself:

“…with more than 3,000 pages and 5,000 image files, Veikko’s Blur Page is the biggest Blur site and perhaps one of the most comprehensive fan sites ever created. The site has around 10,000 visitors per month, making it the most popular Blur site along with the official one.”

Guitar tabs, song lyrics, tour dates and complete ‘gigographies’, VBP’s claim to comprehensiveness is not one to be taken lightly. Not only did Veikko endeavour to document the past of the band, but also the solo careers of its members. In Damon Albarn’s case, of course, there’s a lot of ground to cover there, with a huge variety of disparate solo projects to discuss. But even in the more modest case of Dave Rowntree – the band’s drummer who, until recently, had a very limited solo presence – the page documented any information it could find on his work, from film scores to uncredited Gorillaz appearances.

My favourite section of the site, the “Gigography” index, has not been captured on the Wayback Machine. I was devastated to learn this, knowing that had I been in the loop I probably could have saved a lot of the pages myself. The Gigography was a really interesting section, listing every single live performance that Blur had ever done – from the very first amateur shows all the way to their Wembley comeback. Charting their journey across the country, the attention to detail the timeline rigorously upheld even when drawing on very limited sources was a commendable accolade.

Now all that history is gone. Whether or not it will be reposted, we can’t be sure. Any attempts at emulation are unlikely to parallel Veikko’s quality unless a lot of time and resources are sunk into such an effort. That was the great thing about Veikko’s page – it adhered to one simple rule: “Quality over quantity”

Although the site statistics seem pretty high, the motto has always been “keep it simple”. For example, there is no point in putting thousands of poor quality pictures or articles to the site. Every information piece that is added gets carefully reviewed to meet the Veikko’s Blur Page’s standard.

Sadly, therein lies the problem. All this time and energy, for what? All this attention to detail, double-checking and quality-controlling, just to get wiped off the earth by some ominous corporate force. Veikko and his volunteers worked tirelessly on this website to make it accessible, interesting and comprehensive, all at zero cost to fans of the band.

The sporadic nature of captures on the Wayback Machine mean it cannot be a proper substitute for the site itself; even if every page were documented, different saving dates would lead to contradictions and outdated info. We cannot put the whole world on the Internet Archive – especially since it is now facing bogus legal battles of its own against zealous publishers who choose not to understand how a library is supposed to work. Pair this alongside Ubisoft’s recent claim that consumers ‘should get used to not owning their games’ (and their future takedown of The Crew, a whole other debacle) and we are moving closer towards that dystopian digital world that we all ought to fear: ‘you will own nothing and you will be happy’.

The crisis here is that we are moving closer to a world where we can’t even own knowledge. VBP was a completely non-commercial effort. It had no ads and did not request donations. It was run out of pure love for the band, keeping the Britpop flame alive and holding info about an important part of British culture. Some might see wikis like this as trivia goldmines, with little salience outside of obscure facts that prove superfan status and help in some pub quizzes…but so what?

What’s wrong with knowledge for knowledge’s sake? How are we meant to know in advance which trivial facts will become important markers in the history of cultural analysis? While most of VBP won’t exactly be turning the tide for internet and music historians however many years from now, it’s impossible to predict which of it’s now missing parts could have otherwise been crucial in a broader pursuit of the Britpop canon.

Wiki-style pages like VBP are amazing. We need more of them. They’re simple, elegant, and rigorous. But unfortunately in the current internet ecosystem, they aren’t sustainable. They are run by fans, for fans – they are not run by lawyers, nor do they have financial backing to navigate legal crises. There’s no money in it for any attorney, no matter how much they might want to pitch in for their favourite 90s band. These contributors have lives of their own, and don’t have time to campaign against corporate greed or fight for a freer internet.

Worse still, B-tier wikifarm competition soon swoops in when wiki’s like VBP are lost. Fandom is the most erroneous contributor to this, with new wikis popping up on the farm every single day. Littered with irrelevant ads, containing poor customisation options, with weak moderation and no real sense of community, Fandom sites are quickly becoming the dominant source of information for research on movies, games, and bands like this one.

Mossbag talks about it a lot more and in better detail than this – but from where I’m standing, it looks like the moment that money is involved, sustainability issues disappear. While the information on Fandom is sub-par at best, its relentless advertising creates a mutually beneficial relationship between rights holders and the wiki-hoster; the wiki-hoster can push whatever new product the rights holder is bringing out, even if otherwise irrelevant to the Fandom page itself.

Meanwhile, fully customised wiki sites with zero fluff and a keen focus on quality are left at the mercy of DMCA requests, even though they do not seek to make any commercial gain whatsoever and serve as important sources of reliable information on otherwise niche topics. As the ‘old internet’ becomes more fragmented and the majority of online traffic continues to hit an ever smaller number of providers, nobody will be out here to stand up for the little communities.

I don’t have any parting advice, really, or a path forward to help preserve high-quality resources from going under in the future. Some kind of expansive and non-commercial wikifarm rival to Fandom could go a long way towards combating this problem, but is likely to get hit with plenty of copyright problems of its own; its prospective staff would forever be bogged down in legal tangles.

It does not help, in the UK’s case at least, that copyright law is not keeping pace with an ever-changing internet. It has not kept pace for a long time now, and we will always be bickering about it. VBP should be exempt under fair dealing and fair use in accordance with UK copyright law (as material is reposted for both educational purposes and review purposes, without any commercial gain being sought), although I’m not actually sure what legislature the Finnish-run site is technically beholden to.

As for Blur itself – it is unlikely that anything of such a high quality will replace Veikko’s Blur Page. Blur as a band are too late in their life cycle to get that kind of treatment now; unless Blur becomes the main project of Damon Albarn over the next few years (an exceedingly unlikely prospect), then it will be too inactive to attract such devoted wiki-writing attention. All I can do is remind people: save screencaps of the websites you like on the Wayback Machine before it’s too late.